My local public library deeply irritates me. First, there is the removal of all the call numbers and the senseless arrangement of subjects in the nonfiction section. It doesn’t even correspond to Dewey Decimal subject organization. (Or Library of Congress; I know, I asked.) It supposedly makes it easier for patrons because, “it’s more like a bookstore.” It does not. It makes it more frustrating, and my cynical side thinks it’s on purpose to drive down non-fiction circulation to justify culling the physical books from the library. But maybe I’m tipping my hand too early.

Second, the physical collection has shrunk massively over the last 20 years. I don’t have data, because I don’t think they are publishing it, but I just walk around and look. There used to be shelves of non-fiction on multiple floors. Now it’s just part of the third floor. There are a lot less books and a lot more computers and just open space. The bookshelves are also shorter than they used to be. Less room for books. Probably more accessible for vertically challenged people.

Now I admit, I have an atypical relationship with libraries. It really started in college, and it hasn’t improved. Being among “the stacks” as the rows of bookshelves are often called in large libraries was, and continues to be, a soothing experience. Just to be surrounded by that much work, that much potential knowledge. To be in a place of discovery. It is a refuge and a wilderness.

But that experience is harder and harder to find. Before COVID, I would occasionally go to the University of South Carolina’s main library, all the way to the lowest subterranean floor where the call numbers start, like seeds buried deep underground. I prefer the “B” range in the Library of Congress classification. Philosophy and Religion. That’s where I’ve spent most of my life, intellectually speaking. It’s timeless. I have friends there.

But libraries are not what they used to be. Today, more and more of a library's “collection” is not books. It might be “digital editions” of books, but even that is diminishing. You can also now check out “things” like a kite, a microscope, a mixer, or a demolition hammer. This seems a betrayal of what a library is meant to be. (I can maybe get behind the microscope, but that’s it.)

58.75% of American public library collections are now digital. (Rizzo, 2022) Some see this as a good thing, making “content” more accessible. Now you can just log into your library and access what you want without ever having to darken the door of the library. An understandable urge as they increasingly become de facto homeless shelters—at least the downtown branch. But that’s not what libraries are for.

This is a dark cloud, and it does not have a silver lining.

First, and most obviously, digital content is expensive and it requires ongoing expense. Most libraries are not running their own content servers, but pay large subscription fees to services like Overdrive, Hoopla, and others to give “content” access to their patrons. They don’t own the “content” anymore either. Not like when they buy a physical book to add to the collection.

It might be worth the increased cost if digital editions lasted longer. It seems they should. Bugs, mildew, water, patron loss or theft can’t happen with an e-book. But digital books disappear faster than physical books.

The oldest print book I have in my home library was printed 80 years ago. It still works just fine. I can pick it off the shelf and read its words just like the brand new book published this year next to it. Have you tried to read a 10-year old e-book?

Digital formats go obsolete at an alarming rate. Do you have any documents on a floppy disk written in a DOS-based program? Good luck. CD-ROM is almost as obsolete now. Music is even worse. Can you still listen to your 8-tracks? Sure, vinyl is seeing a bit of a resurgence, so that’s cool, but what about your cassettes? CDs still work if you have a CD player anywhere. Probably you don’t. We all bought MP3s for a season, but then that device died and we lost them all, so we have largely fallen victim to subscription-based streaming services to access music. Music that you could have bought at least in 4-5 different formats already if you’re old enough.

(Monroe 2024)

But this cloud gets even darker.

There are numerous downfalls of the ebook format; if the book is suddenly made into a television show or movie, the classic cover will be automatically updated, and there is no way to stop it. Sometimes, a book will be edited for spelling or grammar mistakes, and the update will be pushed out automatically to everyone who purchased the book on Kindle or Kobo. (Kozlowski, 2023)

Sure, that’s annoying, but most people are willing to make the trade-off to be able to get the book they want almost instantly. But you forgot, I said darker, not just annoying to grumpy old men like me.

Owners of Roald Dahl ebooks are having their ebooks automatically updated with the new censored versions containing hundreds of changes to language related to weight, mental health, violence, gender and race,” reports the British newspaper the Times. Readers who bought these versions, such as Matilda and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, now have the censored versions. (Kozlowski, 2023)

Remote censorship. Let that sink into your bones for a minute. It doesn’t matter what corner of the political universe you reside in, that should send a shiver down your spine and make you clutch your favorite hardcover to your chest in fear like you would your child after hearing of the death of a neighbor’s child. Consider this from J. Budziszewski:

The next destruction of books will take place as swiftly as the burning of the Great Library of Alexandria. Already libraries are getting rid of physical books and shifting to electronic records. Vandals will delete electronic books by hacking the systems; politicians will delete them for the supposed protection of the republic. Selective electronic book burning will be as easy as pie, because so-called artificial intelligence will be used to scan millions of manuscripts at once for unapproved ideas. (Budziszewski, 2024)

J. Budziszewski is a solid, rational thinker. He is not a conspiracy theorist, he’s a tenured professor. In fact, he has written several times that he doubts most conspiracy theories because he realizes how hard they would be to perpetrate. But consider that it is just a micro-step from making the characters in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory no longer fat and obnoxious to deleting whole categories of books. It requires no new technology, just someone to write the code to do it.

It’s enough to make one cry out with Job, “Oh that my words were written! Oh that they were inscribed in a book! Oh that with an iron pen and lead they were graven in the rock for ever!” (Job 19:23-24 RSV-CE)

But the nightmare fodder doesn’t stop there.

AI, so-called “artificial intelligence,” is now “writing” books. An author relates the scenario he found himself against recently. He discovered a title with his last name and that of another author in his field whom he knows. But their first names were transposed. Neither of them wrote the book. Here is his theory as to what happened.

The book is written by AI.

The people behind it attribute the book to two authors based on us, switching our first names so that no direct impersonation can be proven—ensuring that the book always comes up in the results when somebody does a search for either of us.

Needless to say, these two authors do not exist.

The intent is to fool readers and divert them from anything we've written to some crappy AI book. (Gioia, 2024)

Sadly, this is probably not an isolated incident. In fact, the more popular and published an author is, the bigger target she becomes because there is more material for the algorithms to glean cues from to create cheap imitation works as well as an already proven market for that author’s work.

But misinformation is hardly a new phenomena. My wife and I watched Slaves and Kings: The Story of St. Anthony Mary Claret recently. It’s a story about the 19th century Spanish bishop told through the eyes of an early 20th century Spanish writer who had written a novel based on him–or so the thought. He is approached by a priest and asked if he’d write an article about the Bishop to support the effort to canonize him. He initially turns it down, but based on the priest’s comments starts looking into the story and discovers that the Bishop was part of a large smear campaign by his secular opponents in Spain–one that had colored his own perception of Claret when he wrote his novel.

Even physical books can be wrong. But they can’t be remotely changed. Or destroyed. Sure, regimes have burned books for ages, but it takes a lot of work to find the hated books and collect them and set fire to them.

Finally, long-form, physical reading is not the same as reading on a screen. We know this intuitively, don’t we? I think we used to, maybe we’ve forgotten as a society.

The vast majority of the online content you consume today won't improve your understanding of the world. In fact, it may just do the opposite; recent research suggests that people browsing social media tend to experience “normative dissociation” in which they become less aware and less able to process information, to such an extent that they often can’t recall what they just read. (Gurwinder, 2022)

The problem is, this behavior generalizes, like a cancer metastasizes. It makes it hard to focus on, or retain, physical reading or even interpersonal conversation.

We now live in a state of constant distraction caused by an addiction to useless information, and this distraction is so overpowering it even distracts us from the fact we're being distracted.(Gurwinder, 2022)

It’s like becoming so enmeshed in pornography that real flesh and blood women no longer interest you. Like subsisting on Taco Bell and Dippin’ Dots so long that real food no longer is appetizing.

I notice this in my own life. I hope you notice in yours. Not that I hope your brain has been fragmented by the distraction economy; I just assume it has because you’re alive in the United States right now. I pray we become deliberate in our intellectual intake, and seek our intellectual output to be worthwhile for ourselves and to any who may receive it. May we seek truth, not likes. May we cultivate knowledge that will endure and let’s support those who are trying to do the same.

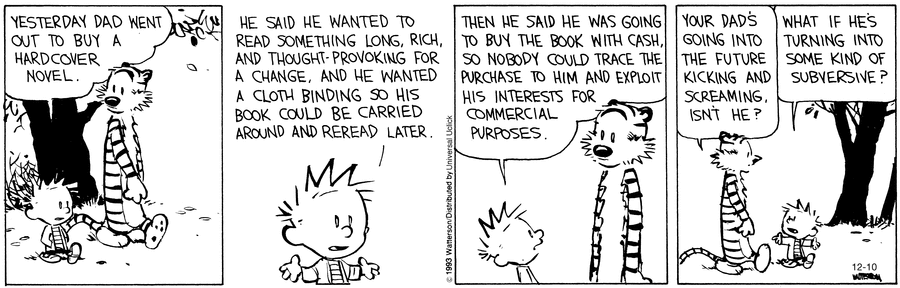

(Watterson, 1993)

Works Cited

Budziszewski, J. (2024) “The Next Burning,” The Underground Thomist, | http://undergroundthomist.comhttps://undergroundthomist.org/the-next-burning

Gioia, T. (2024, February 21). _Help!—AI Is Stealing My Readers_. Honest-Broker.com; The Honest Broker. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/helpai-is-stealing-my-readers

Gurwinder. (2022, May 17). “The Intellectual Obesity Crisis”. Substack.com; The Prism.

Kozlowski, M. (2023, March 6). “Roald Dahl ebooks being updated automatically with censored versions”. Good E-Reader; https://goodereader.com/blog/kindle/ronald-dahl-ebooks-being-updated-automatically-with-censored-versions

Monro, R. (2024) “Digital Resource Lifespan,” XKCD, https://xkcd.com/1909/

Watterson, B. (1993, December 7). Calvin and Hobbes for December 07, 1993: GoComics.com. https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1993/12/07

I have 4,000 books. Not as many as some - but more that most. I also have DVDs, Blu Rays, and pdfs. One needs the old and the new.

Sometimes, the simplest technology really is the best (we don’t usually think of a book as technology, but it is!).